By any definition, Steven C. Wyer was a savvy marketer and brand creator. In the course of three decades, the Nashville entrepreneur had worked in TV production, started a nutritional-products company, and founded a direct-marketing firm. Later, he branched out into real estate, insurance, and financial services. He’d accepted business awards, won praise for creating jobs. The Nashville Chamber of Commerce inducted him into its hall of fame.

So it was strange that, sometime around 2005, Wyer’s numbers started to slip. “We were losing business,” he recalls, “but we didn’t have anything to attribute that to.” Then one day a client asked him if he’d ever Googled his own name. Wyer (somewhat shockingly) never had. So he did—and discovered in a millisecond why business was down.

Years earlier, the SEC had challenged the capital-raising methods of one of Wyer’s firms. Wyer had been exonerated and had since figured the story had gone away. It hadn’t. In fact, the old allegations were sitting right there at the top of his search results. “We’d prevailed in court,” Wyer says, still audibly frustrated, “but because government sites have high authority in search results, the information had lingered for years.”

The fact that Wyer had been found blameless didn’t appear until page four of the search results for his name. Who was going to see that? Clearly, Wyer had a problem. But he’d also stumbled upon the inspiration for what would become his next business: a foray into the new and largely unexplored realm known as online reputation management.

Today, Wyer runs a firm called Reputation Advocate—and he’s got plenty of company. There’s Reputation Armor, Reputation Friendly, and Reputation.com. And while there’s no official tally of the number of firms like this, one reporter who recently attempted to count them all gave up at 74. Clearly, online reputation management is an idea whose time has come. “In the last two or three years, we’ve seen a proliferation of these companies,” observes Andy Beal, CEO of social media tracking company Trackur and the author of Radically Transparent: Monitoring and Managing Reputations Online.

“The more that online becomes integrated in our lives, the more important it will be to have an integrated reputation,” adds Zeus Kerravala, a senior executive handling research at the Yankee Group. “There’s a need for these services now.”

With the dominance of social media, online dialogues have obliterated the days when a brand’s reputation was the simple calculus of what its advertising said it was: Winstons tasted good like cigarettes should, Timex watches took a licking but kept on ticking. All of that changed in 2005, when Jeff Jarvis’ Dell Hell—a blog lambasting Dell Computer for selling Jarvis a faulty laptop—captured the world’s attention and reduced a $49 billion tech corporation to a simpering apology machine. Fionn Downhill, CEO of reputation management firm Elixir Interactive, recalls watching Dell Hell unfold: “I remember thinking, ‘Wow, this is going to become a nightmare for brands.’”

The numbers have borne out her prediction. According to research from GroupM, 58 percent of consumers begin their purchasing journeys with a Web search, and nearly a third of them report that what they hear about a brand on social media is enough to make them eliminate it from consideration. A separate study conducted by Oxford Metrica found that 90 percent of consumers trust what others have to say about a brand, and that 83 percent of brands will face some kind of image crisis in the next five years. But wait, you say—our brands are the highest quality and our customer service is top-notch. It makes no difference. According to the reputation management firms contacted for this story—none of whom would name specific brand clients—trouble will come calling no matter what.

“Sixty percent of the time, the attack is competitor-generated,” Downhill says. “A [rival brand] decides to put you in RipoffReport.com. Customers will attack you, too. Some have legitimate complaints—but some are just shitheads.” One recent case taken on by My Reputation Manager involved “an employee who was terminated and wanted revenge,” says operations director Terry Boothman. “So he [went online and] claimed the CEO was a sex offender.”

But the problem need not even be a direct attack. The Web’s propensity to keep old news alive forever can damage a brand’s reputation indefinitely, from something as comparatively minor as a long-ago quarter of fiscal losses to a 20-year-old DUI incident that returns to haunt a CEO just before his company goes public. “Court proceedings are posted online,” Boothman explains. “So say someone had a false accusation made against them. It’s a little hiccup—but that record is permanent, and too often it comes up.”

With that awareness, however, brands have also gradually shed the presumption that they’re helpless to control what’s said online. “The point is not that you can erase a conversation that’s happening about you, but you can dominate the conversation,” says Reputation.com founder Michael Fertik. “Marketers don’t have to feel like they have to surrender—that’s an archaic view.” It’s this quest for control that currently feeds the burgeoning reputation management industry.

But cleaning up a brand’s reputation is a complicated, costly, and occasionally murky business. While reputation firms maintain they’re providing an integral service for the social media age—wresting back control from online mavericks out to do harm—their work is not without critics. “None of these firms can guarantee that they can do anything for you,” says Danny Sullivan, editor-in-chief of Search Engine Land, a website that covers search engine marketing and optimization. Adds Trackur’s Beal: “You’re looking at [spending] thousands of dollars a month in resources, and even then your success rate is going to be in the 20 percent-40 percent range. Depending on your needs and on how bad your reputation really is, [the firms] will either be very successful or not make a dent.”

So here’s the scenario: However it’s happened, your brand’s come under attack and you’ve got a serious image problem. You shell out the cash for a reputation management company (they’re not cheap, but more on that later). What’s it going to do for you?

While the firms that spoke to Adweek declined to divulge proprietary specifics, the process of reputation repair essentially means burying the negative with the positive. It entails creating and posting a ton of content that’s salutary to the brand and hoping it’ll push the negative stuff deep enough into the search results that nobody will notice it. As Boothman says: “Ninety-five to 99 percent of the time we do suppression. Someone’s painted graffiti on the wall saying you’re a jerk. We spray paint on top of that—and keep doing it.”

“Some of these are tried-and-true techniques,” Sullivan says.

How does that process work, exactly? Reputation management firms pull it off in three basic steps, more or less. First, they locate (and, if necessary, create from scratch) the positive content. “The first thing we do is take inventory of what a brand has,” Downhill says. Often, “they have great content that they have not utilized correctly.” Old TV ads sitting in company archives can be posted to YouTube, for example. For its part, Reputation Advocate might generate 30-50 articles (Wyer employs his own writing staff for the purpose) that flatter a given brand client on sites ranging from LinkedIn to those for trade organizations. “It has to be original content and quality content because quality influences page rank,” Wyer says. In light of Google’s recent tweaking of its search algorithms, which have reduced the authority of content-farm pieces, firms are well-advised to create their pieces of editorial. Wyer says that Reputation Advocate never used content farms to start with.

Once a brand has been sufficiently primped and perfumed with this custom content, the firm moves to obtain (if necessary, beg for) as many backlinks as possible, each of which theoretically ups the chances of the brand-friendly content appearing higher in a search. Ideally, Boothman says, “It’s a matter of getting links from other pages that are trusted references.” Though the value of linking to reputable outside sites may be obvious, “we strongly recommend that the brand create its own microsites,” Elixir’s Downhill says, “and then create links between the homepage and those.”

Finally, you juice everything up with social media. “Facebook, Twitter, YouTube videos—we’ll create all that, [then have] the brand do it for itself,” Boothman says. The entire process, he adds, is what he likens to making “a creative little spider web”—covering a wide area, fully interconnected, and (just to stretch the metaphor), sticky.

That’s the basic package, but each firm has its own proprietary tricks. Fertik claims that his team has examined “close to a thousand variables” in its efforts to make sure the preferred content gets top billing.

“We’ve married the concepts of statistics with quantum mechanics and sentiment analysis,” he says. “We have a whole bunch of technology that I don’t know how to explain to you. But technology is the theme of all these operations, and we’ll fix your shit.”

Of course, that raises an important question: How’s a brand supposed to know when its shit’s been fixed? Reputation repair is hardly a wax-on/wax-off process. So at what point—if any—can a maligned brand consider itself redeemed? Is it as simple as when the negative information has finally been nudged to the second page of search results?

In a functional sense, yes. Studies have shown that 90 percent of people searching for something on the Web never venture past the first page of results, and Web users typically visit only the first three results they find. Reputation managers take these boundaries very seriously, and Fertik’s no exception.

“The first and second impressions are what can make or break your reputation,” he says. Hence, if a brand can push the negative chatter onto page two or beyond, it’s pretty much as good as gone.

Gone for now, at least. Reputation management tends to be an ongoing process, which can also make it a costly one. My Reputation Manager charges $625 a month and tries to get everything done in four months. “But it’s not always doable,” Boothman concedes. “The one variable we can’t control is time.” Asked about Elixir’s fees, Downhill says they “run the gamut. We’ve done projects for $10,000 for individuals on up to six figures for brands that have larger issues.”

And larger issues require larger efforts. An article about a scandal involving the CEO of a major public company might have a lot of Google authority, and can’t simply be unseated by a happy little blog authored by the company employees. “You have to create content that’s more relevant than the negative story that’s sensational—and that’s going to be tough,” Beal says. “Unless you’ve created the cure for cancer, it’s going to be hard to come up with something positive enough to move up in the Google search results.”

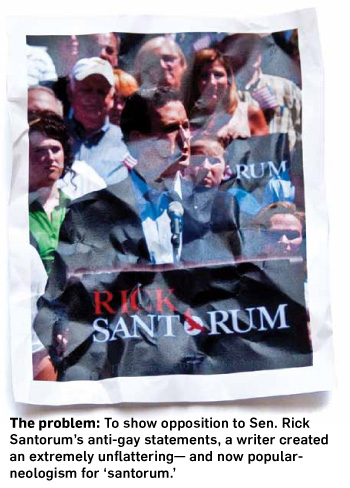

This is why reputation management tactics tend to work better for lesser-known brands with a relatively small bit of defamatory stuff to bury. As Sullivan puts it (using the example of the Pennsylvania senator whose surname has been forever redefined by gay-rights groups), “Rick Santorum is not going to get his problem solved [this way.]”

Nor will many ordinary brands, at least for much longer. As Google continues to refine its algorithms in the never-ending quest to put the most credible information at the top of search results, reputation management techniques that work today may not work a year or two from now. “I don’t know how long-lived these tactics will be,” says Matt Zimmerman, senior staff attorney of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “There will be an arms race between people trying to game the search engines and the engines themselves.”

For now, however, given the poor results that invariably result from brands attempting to haul bloggers or ISPs into court, reputation management is the best card that a troubled brand has to play. Certainly, Wyer thinks so. His business life has stabilized and, down in Nashville, Reputation Advocate is busy these days. Plus, he says, being haunted by a long-ago legal case has given him a pretty effective sales line. “When I talk to people,” he says, “I say, look, if this happened to me, it can happen to you.”  |